For decades, prior authorization has been the blunt instrument of utilization management. Every MRI, infusion, or elective surgery required the same gatekeeping, regardless of whether the ordering physician had a spotless track record or a history of questionable requests. The result : clogged pipelines, overworked nurses, and exasperated providers who felt they were being second-guessed at every turn.

Now, momentum is building toward a different model. Under CMS reforms and state-level initiatives like Texas’s gold-card law, payers are experimenting with exemption programs that reduce or eliminate prior authorization requirements for high-performing providers.1 The idea is straightforward: if a provider’s approval rates are consistently north of 90 percent, why waste administrative energy on rubber-stamping? By shifting clinical oversight to where it’s most needed, payers can cut friction while maintaining safeguards against overuse.

But the simplicity of the pitch belies the complexity of execution. For payer CEOs, the key question is not whether to gold-card providers — it’s how to design programs that are defensible, fair, and scalable in an increasingly transparent regulatory environment.

The Policy Push Behind Gold-Carding

The concept of exempting low-risk providers is not new, but the regulatory winds have shifted. In 2023, CMS’s proposed WISeR (Work to Improve Standardization of Prior Authorization Requirements) framework explicitly encouraged payers to consider differential authorization pathways based on provider performance.2 At the same time, several states — led by Texas— passed laws requiring insurers to exempt physicians from prior authorization if they meet high approval thresholds.

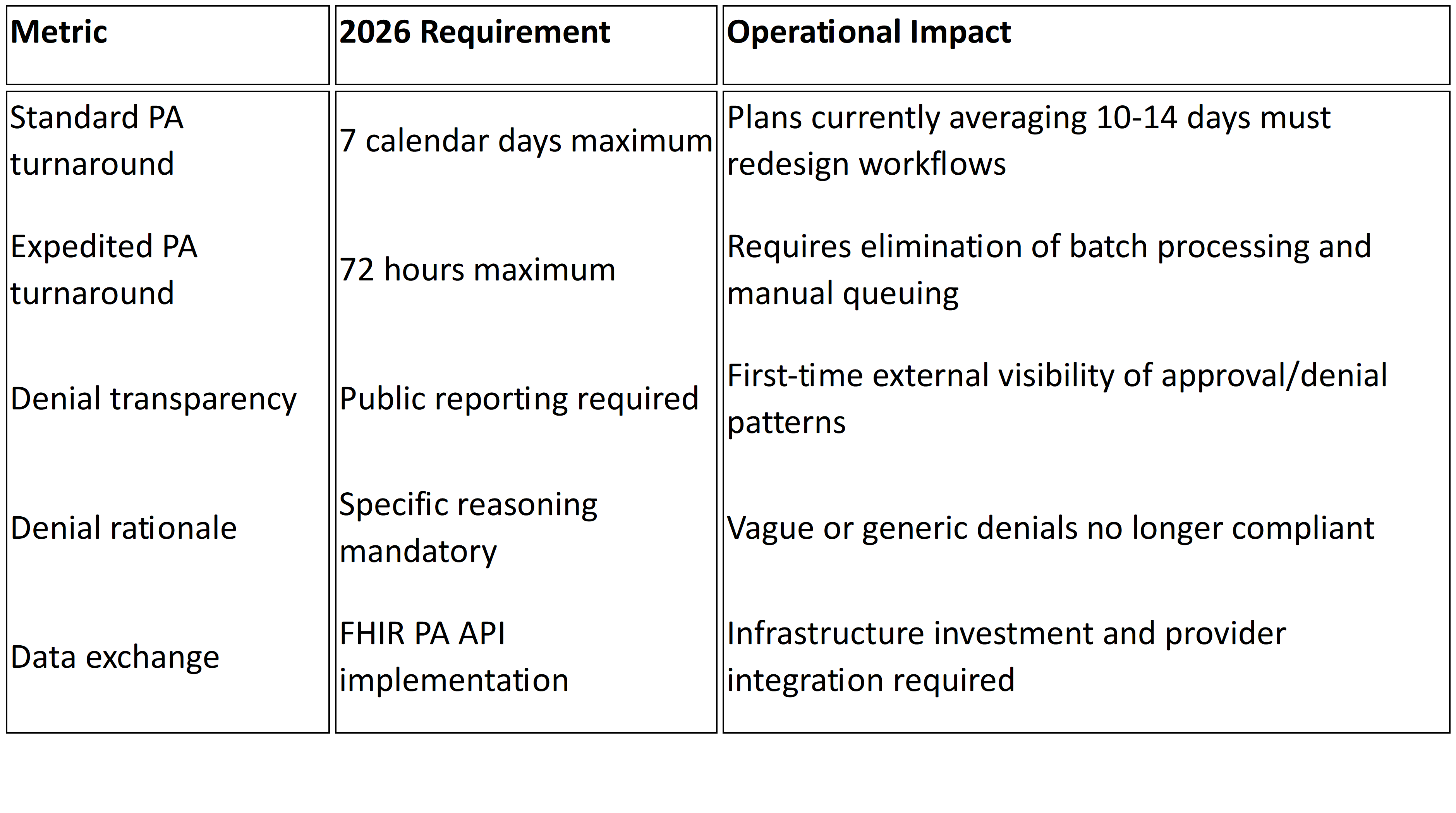

CMS has also signaled that “burden reduction” is now a formal policy objective. In fact, in the 2024 Interoperability and Prior Authorization Final Rule, the agency underscored its intent to reduce unnecessary PAs while strengthening transparency and data sharing.3 For payers, this is not just an option — it’s a compliance expectation wrapped in a market imperative.

Redefining Utilization Management as Risk Distribution

At its core, gold-carding reframes UM from a one-size-fits-all process into a system of risk distribution. High-performing providers are effectively “trusted” to order without friction, while oversight is concentrated on outliers. The potential benefits are significant:

- Faster patient access to care.

- Reduced provider abrasion and administrative cost.

- Reallocation of clinical staff time toward complex, high-risk cases.

But with those benefits come risks. Exemptions, if poorly designed, can lead to unchecked overuse, uneven enforcement, and reputational blowback if patients or regulators perceive favoritism.

The Design Challenge: Fairness, Defensibility, Trackability

Building a gold-card program that stands up to scrutiny requires rigor on three fronts:

- Fairness → Criteria for exemption must be objective, transparent, and consistently applied. Approval rate thresholds should be clearly defined, risk-adjusted for patient mix, and re-evaluated regularly. Otherwise, payers risk accusations of bias or anticompetitive behavior.

- Defensibility → Every exemption policy must be anchored in data that can withstand audit. With CMS now requiring public reporting of prior authorization metrics, payers will need to demonstrate that exempted providers still meet quality and cost benchmarks.

- Trackability → Exemptions cannot be “set and forget.” Payers need real-time dashboards to monitor ordering patterns, detect drift in provider behavior, and quickly revoke exemptions if abuse emerges.

This is where technology becomes central. Without robust analytics and interoperable data systems, exemption programs risk becoming unmanageable at scale.

Providers Welcome It — With Caveats

Unsurprisingly, provider groups have pushed hard for gold-carding. The American Medical Association has called excessive prior authorization a leading driver of physician burnout, with 86 percent of physicians reporting that PA delays care.4 From the provider’s perspective, exemption is overdue recognition of clinical expertise.

Yet even among clinicians, there are concerns. Some worry that tying exemptions strictly to approval percentages may penalize those who care for complex, high-risk populations, where denials are more common. Others point out that exemption does not reduce documentation burden unless paired with true interoperability — otherwise, the paperwork just shifts downstream.

The Strategic Choice for Payers

For payer executives, the decision is less about whether to gold-card and more about how to do it without destabilizing UM. Key choices include:

- Scope: Which service categories are safe to exempt (e.g., advanced imaging) versus too costly or risky (e.g., oncology drugs)?

- Frequency: How often should exemption eligibility be reassessed — annually, quarterly, or in real time?

- Transparency: How much of the exemption logic should be shared with providers, regulators, or even members?

Handled well, gold-card programs can become a strategic differentiator — improving provider relationships, reducing administrative waste, and aligning with CMS’s burden-reduction agenda. Handled poorly, they risk accusations of lax oversight, cost overruns, and regulatory penalties.

The Bottom Line

Gold-carding is more than a provider-pleasing gesture. It is a rebalancing of clinical risk — away from the blanket suspicion of all orders and toward targeted oversight of outliers. For payers, the opportunity is clear: exemption programs can cut costs, ease provider friction, and demonstrate compliance with CMS’s call for smarter, less burdensome UM.

But success depends on execution. Exemptions must be grounded in transparent criteria, backed by auditable data, and monitored continuously. That requires more than policy — it requires technology.

At Mizzeto, we help payers build precisely these capabilities: advanced analytics for provider performance, interoperable dashboards to monitor exemptions in real time, and UM platforms that align compliance with efficiency. For payer CEOs navigating the shift, the choice is not whether to distribute clinical risk — it’s whether to do so with the infrastructure to make it sustainable.